- Quantum Consciousness:

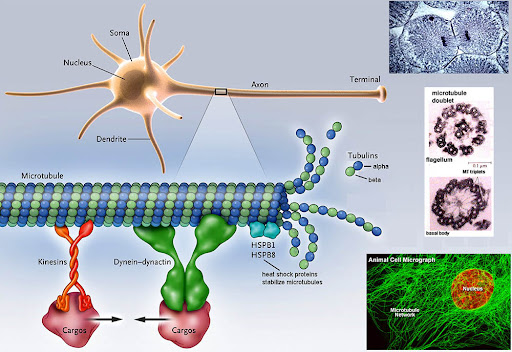

- The Orch OR suggests that consciousness is a quantum process facilitated by microtubules in the brain’s nerve cells.

- Microtubules are protein-based structures forming part of the cell’s cytoskeleton.

- According to this theory, consciousness is akin to a quantum wave that passes through these microtubules.

- Like any quantum wave, it exhibits properties such as superposition (existing in multiple states simultaneously) and entanglement (connection between particles even when far apart).

- Universal Connection:

- Penrose and Hameroff propose that our consciousness can connect or entangle with quantum particles outside our brain, theoretically spanning the entire universe.

- However, other scientists have raised objections. Efforts to recreate quantum coherence (keeping particles in a wave state) only succeed in very cold, controlled environments.

- The brain, being warm, wet, and dynamic, doesn’t fit these conditions, leading to skepticism about consciousness remaining in superposition.

- Criticism and Challenges:

- Orch OR has faced criticism from mathematicians, philosophers, and scientists.

- Key points of contention include Penrose’s interpretation of Gödel’s theorem, the link between non-computability and quantum events, and the brain’s unsuitability for hosting the required quantum phenomena due to its warm and noisy nature.

In summary, Orch OR offers an intriguing perspective on consciousness, suggesting that it emerges from quantum processes within our neurons and may connect with the universe at large¹²³⁴. However, it remains a topic of ongoing debate and exploration in the scientific community. 🌟

Source: Conversation with Bing, 4/23/2024

(1) Orchestrated objective reduction – Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Orchestrated_objective_reduction.

(2) How quantum brain biology can rescue conscious free will. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnint.2012.00093/full.

(3) 14 Orch OR and the Quantum Biology of Consciousness – Oxford Academic. https://academic.oup.com/book/44484/chapter/376471400.

(4) 14 CONSCIOUSNESS IN THE UNIVERSE AN UPDATED REVIEW OF THE “ORCH OR” THEORY. https://anesth.medicine.arizona.edu/sites/default/files/hameroff-penrose_updated_review_of_orch_or_2016_b2237_ch-14_revised-2-3.pdf.

(5) en.wikipedia.org. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Orchestrated_objective_reduction.